ORIGINS

More than 70 countries around the world grow coffee, primarily between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. It is not our intention to source coffee from every single corner of the known world, but rather to nurture relationships in sources where we can develop together, push coffee forward together, and feel proud of the quality of the work that we are doing. We never stop looking for new partners, but we also are not interested in simply putting push-pins on a map.

Each coffee-growing place has its own history, culture, texture, experience, and expectation of coffee quality: We are endlessly fascinated by the differences as well as the intersections and similarities of coffee people and coffee lands worldwide, and we love the journey that coffee takes us on every day.

Read more about green-coffee grades around the world and the origins in which we work by clicking on the links below.

BOLIVIA

BOLIVIA

Capital – La Paz (administrative); Sucre (constitutional)

Coffee Port –Arica, Chile

Producers –Around 12,000 farming families

Approx. Annual Export Volume –30,000 bags

Bag Size – 60 kg

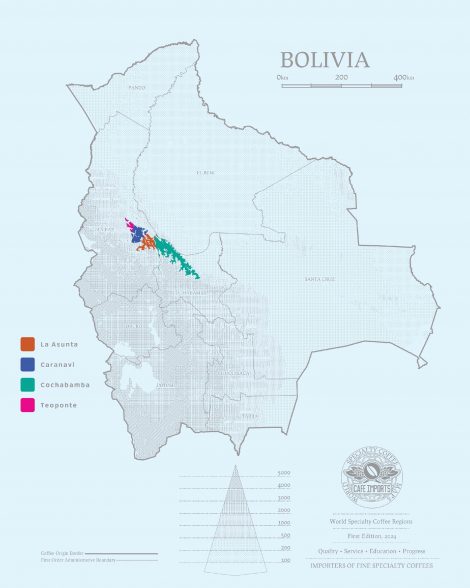

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

- La Paz

- La Asunta

- Caranavi

- Cochabamba

- Teoponte

Common Varieties –Typica, Red Catuai

Drying – Patios, raised beds

Processing Methods

- Natural – Coffee picked, dried in its fruit

- Washed – Coffee picked and depulped, open-tank fermented, washed, dried

Harvest Period

- June-October

Arrival Period

- Jauary – April

La Bodega & Bolivia

We sourced some Bolivian offerings around 2010, but we’ve returned to the country with new relationships and a renewed focus on discovery in the 2021-22 harvest, working with Felix Chambi. Felix is a pioneer in Bolivian specialty coffee, having the only SCA-certified sensory lab in the country called Lata 16. With Felix, we cup lots from the La Paz departments, specifically in the La Asunta and Caranavi municipalities, all within the La Paz department. This area, covered by the mountainous Caranavi forest, has always been the country’s most productive region, but there have been many factors that challenge the country’s consistency, namely high export prices due to being landlocked, mountains that are difficult to traverse, and competition with historically more profitable agriculture. Like all producing countries, though, there is a pocket of committed specialty coffee producers. Expanding our offerings list to Bolivia goes hand in hand with the goal of helping more producers reach our roasting community.

In Bolivia, we see producers who are committed to learning better techniques, growing new varieties, and testing different processes, all while maintaining ecological equilibrium. Farms range in style from coffee gardens like Ethiopia, open-sun like Brazil, and shade-grown like Colombia. Many producers spend time sorting cherries and building processing infrastructure. The offerings range from Organic and Fair-Trade certified to microlots of all processes to Bird-Friendly certified. Many producers, who are part of the indigenous community are very connected in their goal to reach the specialty market.

This rise in specialty-focused production, cooperatives, consumption, and education makes Bolivia a source for new coffee experiences. We are inspired by the producers we’ve met in the Caranavi to continue our sourcing efforts here.

Coffee Production in Bolivia

Exactly how and when coffee came to Bolivia is uncertain. Similar to many other areas of the Americas, coffee was likely brought by enslaved people from Africa. The first records of coffee in Bolivia come from the 18th century through estates in the Yungas region, grown and consumed by the landowners. Later plantations began in the Yungas, but it was never the main crop. Coca leaves grew very well in the region and, at the start of the 20th century, made up 95% of the agricultural market in Bolivia. This prompted a movement to diversify crops to avoid dependence on coca production. With a significant increase in global coffee consumption from around 1970, coffee production expanded more intensively in areas like Caranavi and La Asunta. In the 1980s, with the passage of Law 1008, which regulated coca and controlled substances and defined traditional and surplus coca cultivation areas, coffee was once again considered an economic alternative to replacing these crops. In the following years, several cooperatives and associations were created that would dominate a significant portion of coffee production compared to independent producers. During the 1990s, production levels peaked at around 156,400 60 kg sacks.

Since the record production in the 1990s, Bolivia’s exports have wavered. There was a steep decline to an average of 57,420 60 kg sacks of green coffee by 2016. Despite the lower volume, profits have not decreased terribly, thanks to the shift to primarily fair trade and organic markets. Today, Bolivian coffee production is likely on the rise again. Coffees from the country are in high demand in the specialty market, and local consumption is increasing. New cafes are opening exponentially in larger cities and towns. In recent years, young professionals with knowledge of the “third wave of coffee” have emerged, and more and more people are becoming interested in this topic daily. 12,000 families in the Caranavi depend on coffee as their primary source of income.

Coffee production is also being promoted as part of the National Strategy for Sustainable Integral Development. It is one of the prioritized sectors under the strategic guideline of fostering, promoting, and consolidating the production of competitive agro-industrial products with potential for national and international markets.

Bolivia is ready to enter this new phase, but it requires a comprehensive effort involving everyone from the producer to the barista in pursuit of the common good, which will turn Bolivia into a reference point in the specialty coffee world.

BRAZIL

Capital – Brasilia

Coffee Port – Santos

Producers – 360,000

National Coffee Authority – Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Café (ABIC)

Approx. Annual Export Volume – 40,675,000 bags (2,440,500 metric tons including Robusta)

Production – 1,560 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 60 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Carmo de Minas, Minas Gerais

- 900–1,300 masl

- 300–500 hectares

- Cooked-fruit, coffee-cherry, dark chocolate flavors, lemon/lime acidity, heavy body

Mogiana, São Paulo

- 900–1,100 masl

- 50–300 hectares

- Chocolate, nuts, raisin, wine-like, creamy

Espírito Santo

- Elevation

- 10–50 hectares

- Tropical fruit, floral, sugar cane, bright acidity

Common Varieties – Bourbon, Yellow Bourbon, Catimor, Catuaí Catucaí, Yellow Catucaí, Caturra, Yellow Caturra, Icatú, Maracaturra, Maragogype, Mundo Novo, Obatá

Drying – Patios, raised beds

Processing Methods

- Natural – Coffee picked, dried in its fruit

- Pulped/Pulp Natural – Coffee picked, depulped, dried in mucilage

- Washed – Coffee picked and depulped, open-tank fermented, washed, dried

Harvest Period

- April–September (Minas Gerais, São Paulo)

- October–December (Espírito Santo)

Arrival Period

- November–January (Minas Gerais, São Paulo)

- February–March (Espírito Santo)

La Bodega & Brazil

La Bodega began with a relationship in Brazil: Company founder Andrew Miller imported his first container of coffee in 1993 from a friend’s family farm there, selling bags one by one and personally delivering them—sometimes as far as Chicago.

Today, La Bodega has two primary sourcing relationships, with the exporting companies CarmoCoffees and Bourbon Specialty Coffees. Through these two companies, green-coffee buyer Luis Arocha purchases Serra Negra profile coffees; full-container lots from large and mostly family operated estates; and smallholder microlots as well as experimental and specialty lots based on variety selection or process. Through our connection with CarmoCoffees, La Bodega supports a project called CriaCarmo, which is an initiative providing social, athletic, and academic opportunities for underprivileged and at-risk youth in the Carmo de Minas area.

Coffee Production in Brazil

Brazil has been a coffee-producing benchmark since the mid-19th century, when it surpassed Java as the world’s largest producer. Today, it is still the country by which a vast percentage of forecasting happens (i.e. bumper crop in Brazil means lower prices, but a low-producing year drives prices up), and between Arabica and Robusta it accounts for fully a third of the world’s coffee supply. (About 20 percent of the of its national output is Robusta; it’s the second-largest Robusta origin in the world.)

Because it is responsible for producing so much of the world’s coffee, Brazil’s weather is watched very closely: Incidents of heavy rain or frost in Brazil can make the global commodity price go topsy-turvy almost overnight, as traders and brokers use the country as a benchmark for supply and demand forecasting.

One of the other interesting things that Brazil has contributed to coffee worldwide is the number of varieties, cultivars, mutations, and hybrids that have originated there, either spontaneously or in a laboratory. Coffees like Caturra (a dwarf Bourbon mutation), Maragogype (an oversize Typica mutation), and Mundo Novo (a cross between Bourbon and Typica) are only a few of the seemingly countless coffee strains that were developed or discovered in Brazil, and which have now spread to coffee-growing countries all over the globe.

Farms in Brazil can be more diverse than they are generally depicted, but there is a predominance of comparably huge farms (100+ hectares to 1,000+ hectares) that are harvested mechanically and processed as Naturals or Pulped Naturals in order to produce high volumes of commercial-quality coffee. Espírito Santo is a notable exception to this, as the region’s producers tend to have smaller-size farms (10–50 hectares) and more commonly produce Washed coffee than in other regions, due to the unique climate.

At larger estates, coffee is generally mechanically stripped off the trees using machines that can travel through the rows of plants, shaking off cherries into a collecting vessel as they pass. Most of these coffees will be processed as Natural by being dried in their complete cherries on patios, but others will be processed as Pulped Natural, with the skin of the cherries removed. Raised beds are increasing in popularity for quality purposes, but patio is the primary drying surface here.

Smallholder farmers will also sometimes employ strip-picking techniques, but rather than machinery they will use manual strippers, a piece of cloth that a picker can run along a coffee-tree branch in order to pull off cherries. In some areas, and as attention to specialty coffee–level qualities increases, manual selective picking is becoming more and more of the norm.

BURUNDI

Capital – Bujumbura

Coffee Port –FOT, shipped through Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Producers –700,000

National Coffee Authority –Office du Café du Burundi (OCIBU) National Confederation of Coffee Growers of Burundi (CNAC)

Approx. Annual Export Volume –176,000 bags (10,560 metric tons including Robusta)

Production –300–500 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 60 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Kayanza

- 900–1,300 masl

- 300–500 hectares

- Sugary fruit like fig and peach, rich floral, sparkling acidity like cranberry or citrus

Common Varieties –Bourbon, French Mission, Jackson, Mibirizi

Drying – Raised beds

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, delivered, depulped, open-fermented for 12 hours, soaked for 12–14 hours before the mucilage is removed; then there is a post-wash soak for another 12–18 hours, dried

- Natural – Coffee picked, delivered, rinsed and sorted, dried

Harvest Period

- March–July

Arrival Period

- October–January

La Bodega & Burundi

In 2006, before Burundi had developed a reputation for producing specialty-quality coffees, La Bodega CEO and head of sourcing, Jason Long, took a risk on his first container of microlots from Sogestal Kayanza, paying considerably higher than market price in order to build the relationship. Since then, La Bodega has sourced from Sogestal Kayanza straight through, cupping samples from dozens of washing stations every year and visiting with the director general, Claude Nzambimana, to select the right lots.

Coffee Production in Burundi

Coffee was introduced to Burundi by Belgian colonizers in the 1920s, when it was a forced crop: Farmers were required to grow a government-mandated number of coffee trees—of course receiving very little for their labor or land. Once the country gained its independence in the 1960s, the coffee sector (among others) was privatized, stripping control from the government except when necessary for research or price stabilization and market intervention. The brutal history of coffee under Belgian rule left a bitter taste for many, however, and the crop fell out of favor: As a result, quality significantly declined, and coffee plants were torn up or neglected completely. During and directly following the civil war in the early 1990s, production dropped off considerably, and there was an almost total devastation of the national economy.

The early 2000s saw coffee becoming a tool to recovering the agrarian sector and increase foreign exchange: Inspired in large part by the influence coffee had on rebuilding neighboring Rwanda’s economy after the genocide there, investors began looking at Burundi to re-create that success story. A combination of state-run and private coffee operations emerged, and as access to washing stations was revived, so was producer interest in growing coffee.

The average farm size in Burundi is 1/8–1/4 a hectare, and most producers use that land to grow sustenance crops in addition to coffee. Because of the exceptionally small size of the farms, producers generally deliver their harvest in cherry form to a centralized washing station or CPU (coffee processing unit), including those run by Sogestals—semi-private, semi-government-run networks of receiving and processing stations that might serve hundreds or even more than 1,000 producers during a season.

Producers are paid by coffee weight and their lots are blended upon delivery at the washing station, which means that traceability and transparency are both limited: There is no way to identify which producers’ coffee is in which bags in a lot, and therefore there is no way to pay higher prices to individual producers for their coffee. In fact, paying some of the producers a higher price than others would very likely result in political and social unrest within the communities and among the growers. Therefore, it is important to partner with companies and entities that are known for paying higher overall prices. Coffees are typically bought by La Bodega FOT (Free on Truck) as Burundi is landlocked; the coffee needs to be transported by truck to Tanzania for sea freight.

COLOMBIA

Capital – Bogotá

Coffee Port –Buenaventura, Cartagena

Producers –600,000

National Coffee Authority –Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (FNC)

Approx. Annual Export Volume –10,343,142 million bags (724,020 metric tons)

Production –1,230 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 70 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Cauca

- 1,200–2,100 masl

- 1.5–3 hectares

- Lemon, apple, orange, cinnamon and nutmeg, cocoa

Huila

- 1,600–1,900 masl

- 1.5 hectares

- Tangy cherry, red grape, lime, floral, caramel, berries, cola

Nariño

- 1,650–2,300 masl

- 1–2.5 hectares

- Sparkling, juicy, sweet: tropical fruit and mixed citrus, floral, sugar cane, caramel, almond

Tolima

- 1,500–2,000 masl

- 5 hectares

- Melon, cocoa, almond, citrus, clean, smooth

Common Varieties –Castillo, Caturra, Colombia, Gesha, Pink Bourbon, Tabí

Drying –Casa elba, mechanical dryer, parabolic dryer, patio

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, depulped the same day, open fermented for 12–24 hours, washed clean of mucilage, dried

- Washed, “double” fermented – This processing technique is encouraged by our partners at Banexport: Coffee is picked, stored in a sack, barrel, or hopper for 12–16 hours, depulped, open fermented for 12–18 hours, washed, dried

Harvest Period

- April–July (Main crop: Cauca, Nariño, Tolima; Fly crop: Huila)

- November–January (Main crop: Huila; Fly crop: Cauca, Nariño)

Arrival Period

- September–January (Cauca, Nariño, Tolima)

- March–August (Huila)

La Bodega & Colombia

Colombia is an anchor coffee-growing region for La Bodega, and it’s one where many firsts were born: the Regional Select and Farm Select programs, the Best Cup competitions, and the Decaf De Caña decaf project, to name just a few. Since 2015, La Bodega staff has visited our partners in Colombia more than 15 times per year. The climate here creates overlapping harvest seasons, which means that we are able to source coffee from the country all year long: As a result, we always have fresh-crop offerings from Colombia, most of which come smallholder producers whose coffee is purchased and stratified into quality tiers that are assigned representative prices basis cup score. The model which began in Colombia has become our overall sourcing philosophy: By buying more or all of a producer’s total volume and separating the lots into different quality and pricing levels, it allows producers to plan their sales, invest in their farms, and identify opportunities to grow their business organically and sustainably.

Coffee Production in Colombia

Coffee came to Colombia in the late 1700s by way of Jesuit priests who arrived among the Spanish colonists; the first coffee plantings in the country were in Santander and Boyaca in the north. The plants spread throughout the country through the 19th century, and unlike in many neighboring colonized coffee-producing countries, the average farm size stayed relatively small. Commercial production was somewhat slow-going through until the 1927 establishment of the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (FNC, also called the Colombian Coffee Federation). This NGO coffee authority provided technical and financial support, market access and stability, and, perhaps most importantly, a robust marketing arm: The FNC created the Juan Valdez “character” in the 1950s to promote Colombian coffee, and has expanded the brand into a chain of cafés in-country to support domestic consumption as well.

The average farm size in Colombia is less than 2 hectares, with about 90 percent of the producing population identifying as smallholders. Many producers own their own wet-milling equipment and will depulp, ferment, and dry or partially dry coffee on their own land. Members of cooperatives will sometimes share more centralized processing facilities. Large estates are less common here than in most other coffee-producing countries in the Americas.

COSTA RICA

Capital – San José

Coffee Port –Puerto Moín

Producers –38,804

National Coffee Authority –Instituto del Café de Costa Rica (Icafe)

Approx. Annual Export Volume –923,489 bags (63,720 metric tons)

Production – 1,150 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 69 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Central Valley

- 1o00–1,500 masl

- 2–5 hectares

- Articulate fruit flavor, floral, complex, sparkling acidity

Tarrazú

- 1,200–1,700 masl

- 2.5–5 hectares

- Citrus acidity, toffee or brown-sugar sweetness, clean, green grape, cherry, cocoa

West Valley

- 1,200–1,700 masl

- 2–6 hectares

- High percentage of CoE winners for the complexity, florality, and rich fruitiness of the cups

Common Varieties –Catuaí, Catucaí, Caturra, Costa Rica 95, Gesha, Icatú, SL-28, Sarchimor, Venecia, Villalobos, Villa Sarchi

Drying –Greenhouse, mechanical, patio, raised beds, tarpaulins

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, depulped and demucilaged, dried (Note: Because of water restrictions established by the government and enforced by Icafe, Washed coffee is done mechanically throughout the country)

- Honey – Coffee picked, depulped, dried in mucilage

- Natural – Coffee picked, floated/sorted, dried

Harvest Period

- December–April

Arrival Period

- May–July

La Bodega & Costa Rica

La Bodega‘ presence and relationships in Costa Rica are unique to any other producing region, as we have a full-service export-import arm in San José that manages contracts, samples, shipping, payment, and correspondence with producers throughout the country: Oxcart Coffee–La Bodega Latin America. Being both the importer and exporter of these coffees allows La Bodega to pay farmers directly and more quickly than if there were an outside partner involved, as well as expedites the cupping and approval process.

Coffee Production in Costa Rica

Coffee was planted in Costa Rica in the late 1700s, and it was the first Central American country to have a fully established commercial coffee industry: By the 1820s, coffee was a major agricultural export with economic significance to the population. National output was greatly increased by the completion of a main road to Puntarenas in 1846, allowing farmers to more readily bring their coffee from their farms to market in oxcarts. These oxcarts remained the primary way smallholders transported their coffee until the 1920s, and they remain the national symbol in honor of how integral coffee has been to the country’s development.

In 1933, the national coffee institution was founded thanks to law 2762, which was designed to protect and promote the coffee industry and all of its participants. Instituto del Café de Costa Rica (Icafe) was established as an NGO to assist with the agricultural and commercial development of the Costa Rican coffee market.

One unique aspect to coffee in Costa Rica is the complete transparency along the supply chain, as regulated and enforced by Icafe. Extension service employees visit every mill in order to take volumetric measurements and make predictions about annual output, which prevents fraud and coffee-withholding (it is illegal to trade past-crop coffee; it’s also illegal to grow Robusta). There are also strict mandates about payment: Pickers make a nationally established minimum wage (roughly 1100 colones per 100-kilogram bag), farms are guaranteed 77.9 percent of the FOB price on every sale, and every producer in the country is required to publish their sales prices in multiple national newspapers. Icafe also collects witness samples of every coffee before export and takes mandatory water samples from every farm and mill at the beginning, middle, and end of each harvest season for environmental-protection purposes.

The majority of coffee is grown on small farms, smaller than 5 hectares in size. Until the 2000s, all coffee in the country was processed as Washed: Farmers harvested their coffee cherries and would deliver them intact to a cooperative or a centralized mill, where they would be processed. In the early 2000s, a “micromill revolution” began as producers started to invest in their own wet-milling and processing equipment, which allowed them to capture more of the added value of their product and create unique individual brands. Today, while Washed coffee is still the predominantly recognized profile for the country, more and more producers are experimenting with and refining their alternative processes such as Honey and Natural, among other variations.

All coffee in Costa Rica is traded by volume rather than weight, as ripe cherries are twice the size of unripe cherries (but weigh less). This is a quality-control initiative encouraged and enforced on a national level: The coffee institution, Icafe, has strict regulations dictating the measurement and allowable quality of exportable coffee. The standard unit of measure for coffee cherry in Costa Rica is called a fanega (approx. 250 kilograms), which is the name for the metal box in which coffee cherry is received and tabulated at each mill.

One last note about Costa Rica’s coffee production is to mention that while the Washed process is the most famous and still the most commonly found post-harvest methodology, there is an increasing amount of Honey and Natural being produced as well, as farmers continue to seek differentiation in a competitive market. Washed coffee is generally produced mechanically, to boot: Strict regulations about water usage has forced producers to become creative, and demucilaging machines have not only significantly reduced the amount of water required for processing but has also given rise to the use of Honey processing techniques. Honey coffees are created by depulping but not demucilaging the coffee seeds, and then allowing the mucilage to ferment and dry around the seed before being removed along with the parchment just before exportation.

D.R. CONGO

Capital – Kinshasa

Coffee Port –FOT, shipped through Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Producers – 12,000

National Coffee Authority –L’Office National du Café (ONC)

Approx. Annual Export Volume –300,000 bags (18,000 metric tons including Robusta)

Production – 250 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 60 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

North Kivu

- 1,400–2,00 masl

- 1–2 hectares

- Warm baking spices, cherry and berry, sweet citrus, floral, smooth mouthfeel

Common Varieties –Bourbon, Bourbon Mayaguez, other Bourbon derivatives

Drying –Raised beds

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, delivered, depulped, open fermented (10–14 hours), soaked (12–16 hours), washed in canals, soaked again (12–14 hours), dried

Harvest Period

- March–July

Arrival Period

- October–December

La Bodega & D.R. Congo

La Bodega‘ primary partner is SOPACDI (Solidarité Paysanne pour la Promotion des Actions Café et Development Intégral), a cooperative organization that represents around 11,600 producers through 21 subgroups and was the first cooperative to achieve Fair Trade certification in DRC. The organization was founded by Joachim Mungaga in 2002: Because Joachim is a farmer himself, he recognized the need for improved market access, technology, and agronomy support that would help them improve quality as well as income. Today, SOPACDI has 35 agronomists on staff to provide assistance to members for no cost, and offer training about composting, liquid bio-fertilizer, soil erosion and nutrition, etc. It also creates social-improvement opportunities such as rehabilitation of schools and payment of school fees, providing hospital equipment, renovating roads and bridges, and providing seasonal employment for more than 200 people and permanent employment for more than 500 women.

Coffee Production in D.R. Congo

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is an emerging producing country of specialty coffee, and still remains under many buyers’ radar. The fourth most-populous on the African continent, DRC is also the second-largest country and incredibly resource-rich; despite this, years of political unrest as well as civil and international war have created a nationwide scarcity of electricity, potable water, and developed roadways that has made agribusiness growth slow. However, DRC’s incredibly fertile soil, high elevations, and high-quality coffee varieties mean there’s no reason it can’t be a major producer of specialty coffees.

Coffee was introduced by Belgian colonists, many of whom owned large plantations with forced local labor working in the fields. When DRC achieved independence from Belgium in 1960, the large estates were broken up in redistribution schemes, creating a large network of smallholders with an average of about 100 coffee trees each, if that. More recently, the establishment of cooperatives, washing stations, and an influx of foreign interest and investment from the specialty-coffee sector has helped the nation’s farms renovate and rejuvenate; today we see great potential in coffees from DRC.

Like many of the other growing regions in East-Central Africa and around Lake Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo can be a challenging source for specialty coffee for several reasons: For one, it has long been thought of as a supplier of more commercial grades. For another, the average farm size is smaller than 2 hectares, and most of the farmers also grow sustenance crops on their land along with coffee, making coffee a cash crop that sometimes gets less attention and can be more difficult to manage on a quality-control level. Traceability to the individual producer is virtually impossible, due to the small yields and the technological remoteness of many farmers; this also means that incentives, such as quality premiums can be difficult to assign to coffee contracts. Building close relationships with cooperatives (such as SOPACDI) and repeat buys from the same washing stations are both key in creating a more sustainable specialty-coffee market.

Farmers here typically deliver cherry to the washing station, where their deliveries are weighed and given a payment receipt. The coffees are blended together at the washing-station level based on quality, and are typically separated into day lots.

ECUADOR

Capital – Quito

Coffee Port – Guayaquil

Producers – 105,000

National Coffee Authority –Junta Nacional del Café

Approx. Annual Export Volume – 387,826 bags (26,760 metric tons including Robusta)

Production – 400 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 69 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Loja

- 1,500–2,100 masl

- 1–10 hectares

- Sweet-savory, tart acidity, mixed citrus fruit, brown-sugar or caramel sweetness

Pichincha

- 700–1,400 masl

- 1–10 hectares

- Caramel, sweet and tart, green grape, floral, smooth texture, medium to medium–light body

Common Varieties –Bourbon, Catimor, Caturra, Pache, Typica, Sidra

Drying – Patios, raised beds

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, either depulped and fermented (12–24 hours) and washed, or mechanically depulped and demucilaged, then dried

- Café en Bola – A traditional method (not utilized for specialty coffee) of processing the coffee by letting the cherries dry on the tree and then removing the layers of fruit down to the parchment Washed – Coffee picked and depulped, open-tank fermented, washed, dried

Harvest Period

- Due to its location relative to the Equator harvest in Ecuador happens year-round but peaks from June–December

Arrival Period

- September–October (but varies)

La Bodega & Ecuador

When La Bodega bought its first half-container from Ecuador in 2012, we were the first company to export specialty-quality coffees from Pichincha, an emerging coffee region north of Quito. Two years later, when the Arabica exports in the country dropped down to 30 containers, La Bodega bought three of them—10 percent of the national total. Senior green-coffee buyer Piero Cristiani has spent several years actively seeking, nurturing, and maintaining relationships in the country, and we see very good and very delicious things in the future of this specialty-burgeoning place.

Coffee Production in Ecuador

Coffee came to Ecuador in the middle of the 19th century, planted in the lower-elevation area of Manabi (500–700 meters), which is still the largest area for Arabica production today. Coffee didn’t become a major commercial venture in Ecuador until the late 1920s. Starting in the first decade of the 2000s, the specialty-coffee boom in neighboring Colombia and northern Peru inspired entrepreneurial coffee producers in Ecuador to invest in good Arabica varieties, improved processes, and advanced marketing strategies such as single-farm, single-variety, and innovative techniques that capture the imagination of specialty buyers.

The topography and geography make Ecuador unique (and sometimes challenging) in other ways as well: Its elevation ranges from sea level all the way above 2,000 meters, and includes a wide variety of landscapes, terroir, and microclimates that make the work of coffee harvesting especially challenging. Selective picking is very difficult because of the country’s location on the Equator: This particular climate means that coffee grows and ripens all year long, and a coffee tree might have branches full of under-ripes, ripe cherry, and blossoms at the same time. This forces a farmer to harvest and hold some coffee until enough has been collected to make a delivery or a contract worthwhile, and it also increases labor costs as pickers are needed for an extended period of time. The cost of living and the cost of production in Ecuador is especially high, which makes specialty-coffee prices necessarily high as well: For that reason in particular, the cup quality certainly needs to be there, leading many producers to turn their attention to improving their methodology.

Producers in Ecuador tend to be smallholders, with 1–10 hectares of land, and about 40 percent of the coffee planted nationally is Robusta. Some producers focus entirely on coffee, while other farmers diversify their crops with things like banana or cacao. Producers may have their own wet-milling equipment, or they may deliver cherry to a mill, cooperative, or exporter for blending. The traditional method for harvesting and processing coffee is “en bola,” where the fruit is left to dry on the tree before being harvested and removed completely, but the best lots are selectively harvested and processed with more control and methodology.

EL SALVADOR

Capital – San Salvador

Coffee Port –FOT, shipped through Puerto Barrios, Guatemala

Producers – 20,000

National Coffee Authority – Consejo Salvadoreño del Café (CSC), Fundación Salvadoreña para Investigaciones de Café (PROCAFE)

Approx. Annual Export Volume –400,869 bags (27,600 metric tons)

Production –300–420 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 69 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Chalatenango

- 1,000–2,000 masl

- 1–3 hectares

- Sweet and tangy, apple/apple cider, warm spice, lime acidity, creamy body

Santa Ana

- 1,000–1,800 masl

- 3–10 hectares

- Sweet, toasted nuts, chocolate, toffee, butterscotch, soft lemon-lime acidity, mild cups

Common Varieties – Bourbon, Catuaí, Caturra, Maragogype, Pacamara, Pacas

Drying – Patios

Processing Methods

- Washed (Fermented) – Coffee picked, depulped, open fermented (8–30 hours), washed, dried

- Washed (Mechanically Demucilaged) – Coffee picked, depulped and demucilaged by machine (eco-pulper), dried

- Honey – Coffee picked, depulped, dried in mucilage

Harvest Period

- November–April

Arrival Period

- May–July

La Bodega & El Salvador

The smallest country in Central America is another producing region where La Bodega has a personal attachment: Senior green-coffee buyer Piero Cristiani is from El Salvador, and has a family history in coffee, as well as a passion for it himself. Our work there is primarily with smallholder farmers in the northern region of Chalatenango, where the coffee profile is very distinct and dynamic. For the past several years, La Bodega has built a program with the community there, buying parchment coffee at a premium price and contracting the milling themselves. This allows producers to access money for their coffee faster, saves them time and expense in the milling process, and allows Piero to specify the milling and sorting in order to create exquisite custom lots.

Coffee Production in El Salvador

Coffee was planted in El Salvador in the mid-1700s, mostly for domestic consumption by colonists, but it became a stable and important crop over the following century, especially increasing in significance during the late 1800s when the country’s indigo exports where threatened by the development of synthetic dyes.

As the coffee industry grew, government programs designed to increase production through land, tax, and military-exemption incentives created a small but strong network of wealthy landowners who gained control over the coffee market. Additionally, there were individual smallholders who would grow coffee alongside other crops for use or sale, and would deliver their cherry to the larger estates or to mills. By the 1970s, coffee exports accounted for 50 percent of the GDP, but the country was hurled into a civil war for more than a decade, all but stalling out the industry. Many producers abandoned their farms completely, escaping the widespread unrest. In the 1980s, land-redistribution schemes and agrarian reform disjointed the industry further, and caused market decline; more and more farmers fled their land and allowed the coffee to become neglected and overgrown until a peace agreement was reached in the 1990s.

It’s often said that the 2003 Cup of Excellence competition is largely responsible for a new “wave” of interested in Salvadoran coffee, shining a bright light on the special and/or differentiated varieties grown here, such as Bourbon, Pacas, and Pacamara. In part because many coffee farms were left untouched in the 1980s, when other coffee-growing countries were focusing on replacing heirloom varieties with more productive hybrids. The country’s coffee farms still contain a high percentage of heirloom varieties like Bourbon, as well as particular national cultivars like Pacas and Pacamara.

There are both estate farms as well as smallholder networks throughout El Salvador, with most of the larger commercial activity centered around Santa Ana in the west, in Apaneca-Ilamatepec. In the northern region of Chalatenango (Alotepeque-Metapán), the average farm is smaller than 3 hectares, and many produce as little as 15 quintals (roughly 1,500 pounds of parchment coffee, or 9 exportable bags of green). Producers often own their own small wet-milling equipment, and will deliver coffee in parchment to a mill or exporter for blending. Traceability is much easier with the large estates, who have their own brands and marketing capabilities; the very small farms in areas like Chalatenango mean that historically, producers would never have enough volume to export their own coffee, or even to market it cost-effectively.

ETHIOPIA

Capital – Addis Ababa

Coffee Port –via Djibouti City, Djibouti

Producers –700,000

National Coffee Authority –Ethiopia Coffee and Tea Authority, Jimma Agricultural Research Center

Approx. Annual Export Volume –3,976,000 bags (238,560 metric tons)

Production –720 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 60 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Guji

- 1,750–2,100 masl

- 1/2–3 hectares

- Apricot, tropical fruit and florals, cane-sugar juice, chocolate, citrus acidity

Limu

- 1,100–1,900 masl

- 1/4–1 hectare

- Lemon and lemon candy, stone fruit, floral, melon, cocoa

Sidama

- 1,400–2,200 masl

- 1/4–2 hectares

- Strong fruit flavors, berry, cherry, stone fruit

Yirgacheffe

- 1,750–2,200 masl

- 1/4–1 hectare

- Delicate florals, citrus flavor and acidity, tea-like body, honey sweetness

Common Varieties –Dega, Kudhome, Wolishu, 74112, 74110, 74140, 75227, 74165

- Often, varieties of coffee from Ethiopia are described broadly as “heirloom Ethiopian varieties,” owing to the fact that Ethiopia has the largest pool of genetic material within the Arabica species. However, it’s something of a misnomer to say that the varieties are unclassified or unclassifiable, or unrecognizable by the producer or other professionals. Many commonly found varieties today have been released by the Jimma Agricultural Research Center since the 1970s.

- Sometimes, coffees will be described as “Bourbon” and “Typica.” These terms are colloquially used in Ethiopia to describe certain coffee-berry-disease-resistant cultivars but are not generally considered to be genetically equivalent to the Bourbon and Typica varieties found elsewhere in the world.

Drying –Raised beds

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, delivered to washing station, depulped, underwater fermented (24–72 hours), mucilage is removed, soaked (8–16 hours), washed again, dried

- Natural – Coffee picked, delivered to washing station, rinsed and sorted, dried

Harvest Period

- November–January

Arrival Period

- April–June

La Bodega & Ethiopia

Ethiopia is and has long been an anchor origin for us at La Bodega, as is evident in the volume and variety of coffees we bring in from there every year. We work in four growing regions in the country, each with at least one strong buying relationship: Guji, Limu, Yirgacheffe, and Sidama. Since 2017, green-coffee buyer for Africa, Claudia Bellinzoni, has spent from several weeks to several months a year living in Ethiopia in order to cup coffees, approve contracts, visit producers, and continue to strengthen her connections with our partners there.

Coffee Production in Ethiopia

Nowhere does coffee conjure more romantic images than in Ethiopia, the birthplace of Arabica coffee and the home to the “coffee ceremony,” a traditional way of preparing and serving coffee that harks back to its roots as an offering of hospitality and kinship. Unlike in almost every other coffee-growing country, Arabica coffee was not introduced to Ethiopia as a cash crop, but rather discovered and used as an edible energy source for generations before it was transformed into the beverage form we know now.

Coffee has been known to Ethiopians for centuries, perhaps as early as the 9th century, but certainly by the 14th. It is a wild understory shrub in the southwestern forests, and for its early history it was harvested for the meat of the fruit, which was mashed into a pulp and mixed with suet to be eaten for energy. The berries themselves, along with the leaves, could also be chewed for stimulation, and the leaves steeped with water for a boost. The coffee beverage that we recognize today is said to have emerged during the 16th century, when Muslim traders from the Arabian Peninsula are said to have discovered that the seeds of the coffee fruit could be roasted, ground, and brewed to make a drink that would allow them to stay awake for night prayers. This discovery led to the first transplants of coffee being taken out of Ethiopia and used to establish the first commercial coffee plantations in Yemen.

Ethiopia’s own coffee exports started in the 17th century, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that the crop became a significant part of the export economy. Today, it plays a huge role on the international exchange representing around 34 percent of its export revenue, and it’s also significant in the domestic market as well: Ethiopians consume almost as much as, if not more than they export.

The majority of producers own very small plots of land (1/8–1/4 hectare on average), and it is common for coffee to be intercropped with things like beans or yams for household use. There are three primary cultivation styles utilized here: wild forest coffees, which grow without much or any intervention and are harvested by a local community for personal use or sale; smallholder “garden” coffees that are grown as in the description above; and estate or plantation coffees, which are grown on large privately owned land, often with government-granted rights on coffee-growing land that extend past the official property line.

Smallholder producers very seldom own their own processing equipment, and instead deliver cherry to a local washing station for purchase. Coffee is bought at a daily market rate and the farmer is given payment based on weight; the coffee is then sorted into lots by quality, process, and time or day. This type of sorting and bulking of the daily deliveries makes traceability to individual farmers virtually impossible, and can make financial transparency a challenge as well.

The Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) was established in 2008 by the Ethiopian government, with the intention of democratizing marketplace access to farmers growing beans, corn, coffee, wheat, and other commodities. It had been decided that standardization would be the most egalitarian way to improve national economic health and stability in the agricultural sector, as many producers lacked the ability to market their coffee for a fair price. To do this, the ECX stove to eliminate the barriers to sale by giving farmers an open, public, and reliable national market to sell their product to—however, the regulations established along with the ECX mandated that only coffees grown on estates or by cooperative societies were exempt from selling to the exchange. All smallholder non–co-op coffees were required to enter the ECX, at which point their traceability would be escaped. In March 2017, the ECX voted to allow direct sales of coffee from individual washing stations, which not only allows for increased traceability, but also creates the option for importers and roasters to build long-term buying relationships and pay premium prices.

GUATEMALA

Capital – Guatemala City

Coffee Port –Puerto Quetzal; Santo Tomás de Castilla/Puerto Barrios

Producers –500,000

National Coffee Authority –Asociación Nacional del Café (ANACAFÉ)

Approx. Annual Export Volume –3,612,000 bags (216,720 metric tons including Robusta)

Production –1,247 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 60 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Antigua

- 1,300–1,600 masl

- 1–5 hectares

- Soft acidity, cocoa, milk-chocolate sweetness, almonds

Atitlán

- 1,500–1,700 masl

- 1–5 hectares

- Lemony flavor and acidity, nutty, rich chocolate, mild florals

Huehuetenango

- 1,500–2,000 masl

- 1–5 hectares

- Apple, green grape, almond, brown sugar, caramel

Common Varieties – Anacafe 14, Bourbon, Catimor, Catuaí, Caturra, Costa Rica 95, Pache, Sarchimor, Typica

Drying –Patios, mechanical dryers

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, depulped, open fermented (12–36 hours), washed, dried

Harvest Period

- September–April

Arrival Period

- June–July

La Bodega & Guatemala

Strong relationships in Guatemala have been pivotal for building a stratified buying model there, and senior green-coffee buyer Piero Cristiani has lots of time on the ground there to strengthen connections with export partners as well as producers. His marathon cupping sessions have allowed him to not only get calibrated to a T, but also to identify the greatest areas of potential and create quality marks that allow smallholders greater access to a better market share by selling their lots into our Quetzal and Regional Select projects. La Bodega works primarily with smallholder producers in Antigua, Atitlán, and Huehuetenango.

Coffee Production in Guatemala

Coffee came to Guatemala in the late 18th century, as it did to a lot of the neighboring colonies, but cultivation really started gaining steam in the 1860s with the arrival of European immigrants who were encouraged to establish coffee plantations by the government in order to stimulate the coffee economy in the wake of the failure of the country’s main export crop, indigo.

Most coffee farmers are smallholders, and in 1960, coffee growers developed their own union, which has since become the national coffee authority ANACAFÉ (Asociación National del Café), which acts as a research center, marketing agent, and financial organization that provides loans and offers support to growers throughout the various producing regions.

The average farm size is smaller than 5 hectares, with larger estates being present but generally less common than in other Central American countries. Some producers do their own wet-milling on-site at their farm, while many deliver cherry to central processing or receiving mills, either run by cooperatives or multinational export companies. Traceability is relatively achievable from smallholders and from associations, though in some regions it is more common to find bulked, blended lots.

Despite its relatively small size, Guatemala has a lot of diversity by region in terms of not only profile, but also coffee processing: The vastly different terroir from place to place (Huehuetenango to Atitlán, for example) means that while the majority of the country produces Washed coffee, each region has a very different approach to achieving the final product. In the highlands, for instance, fermentation can last up to 36 hours due to cool overnight temperatures; elsewhere, eco-pulping or mechanically demucilaging the coffee seeds is becoming more popular.

HAWAII

Capital – Honolulu

Coffee Port –Kona

Producers – 1,030

National Coffee Authority – Hawaii Coffee Association

Approx. Annual Export Volume – 52,400 (60kg) bags (3,144 metric tons)

Production –861 kg per hectare

Bag Size –100lb

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Kona

- 150–915 masl

- 2–5 hectares

- Soft acidity, mild sweetness, nuts, toffee

Maui

- 100–550 masl

- 200 hectares (there is one large estate on the island, plus about 40 hectares owned by smallholders)

- Nuts, savory chocolate, citrus acidity

Common Varieties – Blue Mountain, Bourbon, Catuaí, Caturra, Typica/Kona Typica

Drying – Patios, raised beds

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, depulped, open fermented (12 hours), washed, dried

Harvest Period

- August–December

Arrival Period

- December–March

La Bodega & Hawaii

La Bodega has been sourcing Hawaiian coffees for many years thanks to a longstanding relationship with producing and export partner who has a close Minnesota–Hawaii connection. While we primarily source lots from Kona and Maui based on grade and quality, we have also brought single-farm offerings to market, and continue to seek the best cups that all of the islands have to offer.

Coffee Production in Hawaii

The only large-scale commercial production of coffee in the U.S. got its start in 1813, when the first coffee plants were brought to O’ahu. For many years, sugar production outshone coffee, but by the time Bourbon variety trees were introduced onto the Big Island in the 1820s, coffee estates were becoming more commonplace.

Over the course of Hawaiian history, coffee has had to compete with sugar for attention and profitability, but it began to really come into its own in the late 20th century as sugar and pineapple production both fell into decline. These days, Hawaiian coffee is typically considered exotic and special both because of its island appeal as well as its price tag: The cost of production is exponentially higher than in other coffee-growing regions due to the high price of labor, materials, land, etc., compounded by the small overall supply available. Hawaii is still both one of the smallest producers of coffee by volume as well as by hectare: There are currently around 3,000–3,200 hectares planted with coffee trees throughout the state, with just over 1,000 active producers. Hawaii produces around 0.4 percent of the world’s annual supply.

While there are still large estates, especially on certain of the islands of Hawaii, there are still a majority of smallholder producers who own between 2–10 hectares of land. (Due to this being a United States territory, however, land is typically measured in acres. One hectare is roughly 2.4 acres.) Many producers have their own wet mills, though on some islands (such as Maui), smallholders deliver cherry to centralized processing facilities. Washed process is most commonly practiced, though Honey and Natural coffees are being experimented with more and more as a way of adding additional value.

HONDURAS

Capital – Tegucigalpa

Coffee Port –Puerto Cortés

Producers –110,000

National Coffee Authority –Instituto Hondureño del Café (IHCAFE)

Approx. Annual Export Volume – 6,046,086 bags (417,180 metric tons)

Production – 1,297 kilograms per hectare

Bag Size – 69 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Marcala

- 1,200–1,600 masl

- 2.5–10 hectares

- Fruity and complex, citrus acidity, cocoa, soft toasted nuts, caramel or toffee

Common Varieties – Bourbon, Catuaí, Caturra, Lempira, Pacamara, IHCAFE 90

Drying –Covered greenhouses (parabolic or otherwise), mechanical dryers, patios, raised beds

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, depulped, fermented (8–18 hours), washed, dried

Harvest Period

- November–April

Arrival Period

- May–July

La Bodega & Honduras

La Bodega‘ work in Honduras has been centered in and around Marcala, which has some of the best-performing coffees and is consistently showing up on Cup of Excellence winners lists. Senior green-coffee buyer Piero Cristiani has found strong partnerships in that region, and continues to explore smallholder coffees from its highlands, where good varieties and cooler temperatures tend to inspire more dynamic cups.

Coffee Production in Honduras

The first recorded harvest year for Honduras was 1804, in the department of Comayagua, but coffee’s early history in Honduras was somewhat slow going as the country lacked the necessary support to grow a thriving coffee industry. Coffee did develop into a significant agricultural export, however, and the early 2000s saw exponential growth—so much so that credit has been given largely to coffee for preventing the national government from declaring bankruptcy during the financial crisis of 2009.

Historically, Honduras has been better-known as a producer of large volume commercial-quality coffee, suitable for mild blender coffees. This has especially been true as IHCAFE has developed and/or distributed new cultivars (primarily Catimor types) with an emphasis on productivity and resistance to disease. In the past decade, however, specialty coffee has begun to come into its own, especially with the development of the CoE contest and the emergence of La Paz in the Montecillos region—specifically Marcala—as a production region with high potential for quality. The top coffees are typically heirloom or older-stock varieties such as Bourbon, Catuaí, Caturra, or even Gesha, though the coffee-leaf rust epidemic has put these at greater risk and encouraged many producers to switch to hybrids like IHCAFE 90.

This country has a mix of smallholder farms as well as mid- and large-size farms, though the average farm size is somewhere closer to 3.5–5 hectares. Some producers have wet-milling equipment on their property, but it is still very common for producers to deliver cherry to a central processing facility, either to a cooperative or to a large mill owned and operated by a transnational export company.

JAMAICA

Capital – Kingston

Coffee Port –Montego Bay

Producers –8,000

National Coffee Authority –Coffee Industry Board of Jamaica, Jamaica Agriculture Society

Approx. Annual Export Volume – 7,714 (70kg) barrels (540 metric tons)

Production –873 kg per hectare

Bag Size –15/30/70kg barrels

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Blue Mountain

- 900–1,700 masl

- 1/4–1 hectare

- Sweet and somewhat mild, nuts, red grape, citrus and citric acidity

Common Varieties –Blue Mountain, Bourbon, Gesha, Typica

Drying – Patios

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, depulped, fermented, washed, dried

Harvest Period

- February–June

Arrival Period

- May–September

La Bodega & Jamaica

La Bodega has partnered with an entrepreneur from Saint Andrew Parish who has his own processing equipment and buys coffee from around 250 of his neighbors and fellow producers, giving them another option to work with a local who understands their situation as well as their desire to earn fair prices and recognition.

Coffee Production in Jamaica

The first coffee exports on record from the country are from 1752, but historically, coffee production has competed with other crops and export goods and until the mid-1940s there lacked real supportive infrastructure for widespread commercialization of the crop. The Coffee Board of Jamaica was created in 1950, and its influence helped not only promote the image and marketing of Jamaican coffee, but also began to provide producers with more resources to increase productivity.

Jamaica has an outsize reputation for coffee production based on its annual yields: The country might contribute 0.15 percent of the world’s coffee supply in a bumper year. Jamaica’s coffee production is highly sought after by the Japanese, which means its relatively small yield still commands a high price—as much as $30 per pound green in recent years.

While there are thousands of smallholder farmers in Jamaica, the coffee market is dominated by two large estates (which recently merged): Wallenford and Mavis Bank. The estates buy coffee in cherry (or cherry-berry, as they’re called locally) as most smallholders don’t have their own wet-milling equipment. The estates then blend the lots with their own coffee and sell them under their own marks. This is because the average farmer owns between 80–150 coffee trees. Despite that longstanding disenfranchisement, there are increasing opportunities for smallholders to operate outside of the estate system.

INDONESIA

Capital – Jakarta

Coffee Ports

- Flores – Jakarta

- Java – Surabaya

- Sulawesi – Makassar

- Sumatra – Belawan

Producers – 1.5 million

National Coffee Authority – Association of Indonesian Coffee Exporters,Indonesian Coffee and Cocoa Research Institute (ICCRI)

Approx. Annual Export Volume – 6,891,000 bags (408,600 metric tons including Robusta)

Production – 808 kg per hectare

Bag Size – 60 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Flores

Bajawa

- 1,200–1,800 masl

- 1–3 hectares

- Lower acidity, cherry or pulpy fruit, some herbaceous flavor, caramel, earthy, heavy body

Java

East Java

- 914–1,828 masl

- 10–2,000 hectares

- Low acidity, heavy body, clean sweetness, cocoa or chocolate, soft nuts like almond

West Java

- 1,100–1,600 masl

- 1–2 hectares

- Medium-low acidity, creamy body, dark fruit, savory, earthy

Sulawesi

Tana Toraja

- 1,100–1,800 masl

- 2–3 hectares

- Cherry, stewed fruit, savory herbs, medium creamy body

Sumatra

Aceh

- 1,100–1,300 masl

- 2 hectares

- Toffee or caramel, sweet cooked vegetables, dark fruit, autumn leaves, heavy body, clean

Common Varieties – Andong Sari, Ateng, Catimor, Jember, Kartika, Lini S795, Timor Hybrid (aka Tim Tim, Bor Bor), Typica

Drying – Patios, raised beds, tarpaulins

Processing Methods

- Wet-Hulled (Sumatra process) – Coffee picked, depulped, fermented, washed, pre-dried (8–12 hours), wet-hulled, dried

- Wet-Hulled (Flores, Sulawesi, Sumatra) – Coffee picked, depulped, fermented, washed, wet-hulled, dried

- Washed (Java, Sulawesi) – Coffee picked, depulped, fermented (12–16 hours), washed, dried

Harvest Period

- Flores – March–September

- Java – July–October

- Sulawesi – May–November

- Sumatra – October–June

Arrival Period

- Flores – October–December

- Java – November–December

- Sulawesi – September–December

- Sumatra – year-round

La Bodega & Indonesia

It can take senior green-coffee buyer Piero Cristiani several weeks on his sourcing trips to fly from region to region for cuppings and to visit partners. His focus is primarily in four coffee-producing areas: Flores, Java, Sulawesi, and Sumatra, where he has the strongest relationships and/or seen the greatest potential.

Coffee Production in Indonesia

Routinely in the top-five coffee-producing countries, Indonesia is almost like a world of its own when it comes to coffee: The transcontinental nation has more than 17,000 islands, many of which grow coffee in widely diverse climates and landscapes. Coffee was introduced throughout Indonesia by the Dutch in the 1600s, having stolen coffee trees from Yemen in an attempt to corner the market with exports to Europe. Today, the coffee-producing landscape across Indonesia is primarily dominated by smallholder producers.

The trading process is somewhat unique here: In some regions, producers deliver cherry to a central location, while others depulp their own coffee and deliver it in its fermented/fermenting mucilage for processing and drying. “Collectors,” or agents who buy semi-dry parchment coffee to deliver to mills, are a unique and significant part of the supply chain here.

Taken as a whole, Indonesia is one of the top 5 coffee-producing countries in the world. The six areas of Indonesia from which most commercial Arabica comes are Bali, Flores, Java, Sulawesi, and Sumatra—each one unique in its terroir, processing, handling, and/or any and all of the above. This makes speaking about “Indonesian coffee” a touch difficult, though there are naturally some similarities from place to place. Here, a short description of the four main growing areas in Indonesia from which La Bodega sources coffee.

Flores: Farmers here tend to have about 1–3 hectares and many are at higher elevation, up to 1,800 meters in volcanic soil. There are several distinct ethnic groups that live on this eastern island, but the Bajawa people are known for their significance as coffee producers. Most farmers here grow sustenance crops such as cassava long with coffee, but coffee is the primary commercial crop. Smallholders here deliver cherry to cooperatives or to central processing facilities, where the coffee will typically be Wet-Hulled and only occasionally Washed.

Java: This island was one of the first islands in Indonesia to produce coffee, and was once the world’s powerhouse of monocultural coffee production. An outbreak of coffee-leaf rust decimated the crop in the 1860s and 1870s, however, which led to the abandonment of many of the Dutch-owned estates. After the redistribution scheme, producers replaced many of the more disease-susceptible Arabica varieties with Robusta, and more recently with hybrid cultivars. While Indonesia as a whole is a large producer of coffee, Java has not recovered its status as a primary contributor of Arabica coffee. The majority of farmers here own small plots of land and deliver coffee in cherry to the four or five large estates that still exist (representing about 4,000 hectares of production). Typically, the estates will buy and blend the smallholders’ coffees to sell under their brand names.

Sulawesi: Formerly known as Celebes, this region is dominated by smallholder, like the rest of the country. About 5 percent of the island’s coffee is produced by seven larger estates. Coffee is delivered in cherry or, more often, wet in parchment, to a central mill or to a collector. It is then most commonly Wet-Hulled, though La Bodega partners with a mill that primarily produces Washed coffees.

Sumatra: Producers here typically own 1 hectare or less, but there are a few larger family farms and a smattering of estates that still exist in Sumatra. This region, however, has a greater predominance of cooperatives than the others, with smallholders coming together in order to simulate an economy of scale, achieve Fair Trade and organic certification, and pool resources as well as product in order to access greater market share.

KENYA

Capital – Nairobi

Coffee Port –Mombasa

Producers –700,000–800,000

National Coffee Authority – Coffee Directorate, also known as the Coffee Board of Kenya

Approx. Annual Export Volume – 860,000 bags (51,600 metric tons)

Production –455 kg

Bag Size – 60 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Embu

- 1,300–1,900 masl

- 1–2 hectares

- Dark fruit, brown sugar, balanced

Kirinyaga

- 1,300–1,900 masl

- 1–2 hectares

- Floral, refined, fruity, complex

Mt. Elgon

- 1,500–1,950 masl

- 10–50 hectares

- Savory with strong tomato, tangy acid creamy

Nyeri

- 1,200–2,300 masl

- 1–2 hectares

- Sugary and tropical, juicy mouthfeel, tart acid

Common Varieties –Batian, French Mission, K7, SL-14, SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Tanganyika Drought Resistant

Drying –Raised beds

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, depulped, fermented (24–48 hours), washed, soaked (12–72 hours), dried

Harvest Period

- August–January (main crop); April–July (fly crop)

Arrival Period

- March–May

La Bodega & Kenya

La Bodega cups around 1,200–1,400 samples of smallholder coffees from various F.C.S. in four primary regions: Embu county, Kirinyaga county, the arear around Mt. Elgon, and Nyeri county. Whenever possible we arrange to purchase coffees from the same factories year after year. Each region has a profile that can be claimed as distinct. In Embu, we look for very balanced cups with citrus fruit and apple as well as a chocolate bass note. Nyeri is more dynamic, lively, and fruity with white grape and a caramel sweetness. Mt. Elgon’s coffees remind us more of tropical fruit, with grapefruit, pineapple, and tropical flowers like hibiscus. Kirinyaga has a classic Kenya profile: cola, black cherry and black currant, lime, and tomato.

Coffee Production in Kenya

Interestingly, Kenya was one of the last places to have Arabica coffee introduced for commercialization and cultivation, despite the fact that it shares a northern border with Ethiopia, coffee’s birthplace: The first plants were brought from the island of Réunion (née Bourbon) by missionaries in the late 1800s, in an attempt to finance their mission work by cultivating and selling coffee. By the 1920s, as Europeans demanded more and more coffee, it became a major cash crop for export, which lead to the establishment of the auction system: Until very recently, all of the smallholder coffee in the country was required to be tendered for sale though a marketing agent who represented the lots through the Kenyan auction. This open-outcry marketing system, established in the 1930s and still operating every Tuesday in Nairobi, made it possible for coffee cooperatives to sell their coffee at a higher premium or differential to the highest bidder. It also, however, made it virtually impossible for buyers to create relationships with sellers, or to guarantee that coffees from the same producers could be procured on an annual basis.

While the bidding is electronic these days, the system itself remains largely unchanged: Farmer Cooperative Societies (F.C.S.) and estates alike need to hire a marketing agent to bring their coffee to the auction. Lots are collected, a catalog is printed to advertise the lots up for bidding, and samples are tendered. On auction day, buyers sit in bleacher-like seating and bid on the lots they would like to purchase. The bidding is silent, but an electronic monitor announces the change in price. This auction system, as well as the complex chain of custody that coffee needs to pass through before reaching the end buyer, are a few of the reasons—quality aside—that the price for Kenyan coffee tends to be higher on average per pound for importers and roasters.

In recent years, the introduction of a “second window” marketing option has opened up avenues for farmers or farmer societies to sell more directly to a buyer by negotiating prices outside of the auction. Many coffee factories and marketing agents still prefer to take a chance on the prices at auction, while others are opting to have more of a close contact and negotiation rights with their buyers.

Smallholders dominate the country’s producer profile, with more than 75 percent of the coffee sector owning fewer than 2 hectares of land. (Additionally, about 85 percent of the country’s farmers are Kenyan natives, though European influence is still evident among the larger estate owners.) Because farmers produce little coffee individually, they typically deliver cherry to a local factory, which is what the washing stations are called. Many of the factories are operated by F.C.S., some of which provide member services such as access to fertilizer, pesticides and other materials. Once farmers deliver to the mill, their coffee is sorted and blended to create lots either by day, quality, region, etc: This makes traceability to the producer nearly impossible in most of the smallholder coffees of the country.

It is interesting to consider the impact that Kenya-specific varieties have had on developing these famous flavor profiles. The most famous coffees from Kenya are known as the Scott Laboratories cultivars: SL-14, SL-18, and SL-32. Scott Labs was hired by the British colonial government of Kenya to undertake a series of tests and develop a catalog of coffee cultivars that would have the greatest potential with regards to productivity, resistance, and quality. Scott Labs scientists worked on more than 40 types, giving them each a number with an “SL” for classifications. The three best-known are SL-28, SL-32, and, to a lesser degree, SL-14: They are given credit for much of what we consider the classic Kenyan profile of black currant and tart fruit, dazzling acidity, and some of the more savory and complex tomato-like characteristics.

Interestingly, Kenya was one of the last places to have Arabica coffee introduced for commercialization and cultivation, despite the fact that it shares a northern border with Ethiopia, coffee’s birthplace: The first plants were brought from the island of Réunion (née Bourbon) by missionaries in the late 1800s, in an attempt to finance their mission work by cultivating and selling coffee. By the 1920s, as Europeans demanded more and more coffee, it became a major cash crop for export, which lead to the establishment of the auction system: Until very recently, all of the smallholder coffee in the country was required to be tendered for sale though a marketing agent who represented the lots through the Kenyan auction. This open-outcry marketing system, established in the 1930s and still operating every Tuesday in Nairobi, made it possible for coffee cooperatives to sell their coffee at a higher premium or differential to the highest bidder. It also, however, made it virtually impossible for buyers to create relationships with sellers, or to guarantee that coffees from the same producers could be procured on an annual basis.

While the bidding is electronic these days, the system itself remains largely unchanged: Farmer Cooperative Societies (F.C.S.) and estates alike need to hire a marketing agent to bring their coffee to the auction. Lots are collected, a catalog is printed to advertise the lots up for bidding, and samples are tendered. On auction day, buyers sit in bleacher-like seating and bid on the lots they would like to purchase. The bidding is silent, but an electronic monitor announces the change in price. This auction system, as well as the complex chain of custody that coffee needs to pass through before reaching the end buyer, are a few of the reasons—quality aside—that the price for Kenyan coffee tends to be higher on average per pound for importers and roasters.

In recent years, the introduction of a “second window” marketing option has opened up avenues for farmers or farmer societies to sell more directly to a buyer by negotiating prices outside of the auction. Many coffee factories and marketing agents still prefer to take a chance on the prices at auction, while others are opting to have more of a close contact and negotiation rights with their buyers.

Smallholders dominate the country’s producer profile, with more than 75 percent of the coffee sector owning fewer than 2 hectares of land. (Additionally, about 85 percent of the country’s farmers are Kenyan natives, though European influence is still evident among the larger estate owners.) Because farmers produce little coffee individually, they typically deliver cherry to a local factory, which is what the washing stations are called. Many of the factories are operated by F.C.S., some of which provide member services such as access to fertilizer, pesticides and other materials. Once farmers deliver to the mill, their coffee is sorted and blended to create lots either by day, quality, region, etc: This makes traceability to the producer nearly impossible in most of the smallholder coffees of the country.

It is interesting to consider the impact that Kenya-specific varieties have had on developing these famous flavor profiles. The most famous coffees from Kenya are known as the Scott Laboratories cultivars: SL-14, SL-18, and SL-32. Scott Labs was hired by the British colonial government of Kenya to undertake a series of tests and develop a catalog of coffee cultivars that would have the greatest potential with regards to productivity, resistance, and quality. Scott Labs scientists worked on more than 40 types, giving them each a number with an “SL” for classifications. The three best-known are SL-28, SL-32, and, to a lesser degree, SL-14: They are given credit for much of what we consider the classic Kenyan profile of black currant and tart fruit, dazzling acidity, and some of the more savory and complex tomato-like characteristics.

MEXICO

Capital – Mexico City

Coffee Port –Veracruz

Producers –500,000

National Coffee Authority –Asociación Mexicana de Cafés y Cafeterías de Especialidad A.C., Consejo Mexicano del Café, Instituto Mexicano del Cafe (INMECAFE, reinstated)

Approx. Annual Export Volume – 1,653,043 bags (114,060 metric tons including Robusta)

Production –382 kg

Bag Size – 69 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Chiapas

- 1,000–1,750 masl

- 1–5 hectares

- Sweet, almond, vanilla, cherry, chocolate

Oaxaca

- 900–1,700 masl

- 1–2 hectares

- Mild, milk chocolate, toffee, lemon, nuts

Puebla

- 1,000–1,750 masl

- 1–3 hectares

- Fruity, lemon and lemongrass, caramel, chocolate, sweet-tart acidity

Common Varieties –Bourbon, Catimor, Catuaí, Caturra, Garnica, Maragogype, Marsellesa, Mundo Novo, Typica

Drying –Mechanical dryers, patios

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, depulped, fermented (12–18 hours), washed, dried

Harvest Period

- November–March

Arrival Period

- May–June

La Bodega & Mexico

La Bodega‘ work in Mexico has focused primarily in the regions of Chiapas and Veracruz, with occasional forays into Oaxaca. In recent years, senior green-coffee buyer Piero Cristiani has concentrated his sourcing efforts in the buffer zone surrounding the Triunfo Biosphere Reserve in the state of Chiapas, where he has developed strong relationships with several conservationist-minded cooperatives.

Coffee Production in Mexico

Like many coffee-producing countries in Mesoamerica, Mexico’s history with coffee traces back to the mid to late 18th century and is dominated by the white European invasion and colonization of the land. Coffee was not as popular a plantation crop in the earliest of days, as other products were more lucrative to produce, however, the beginning of the next century saw an influx of wealthy Europeans establishing large coffee farms, at which point the industry began to take off.

Following the Mexican revolution, land-redistribution efforts established a similar network of dispersed smallholders as existed throughout Central America after different countries won their independence from colonial Europe. There is still a predominance of smallholder producers in Mexico, with most owning fewer than 5 hectares and the majority owning less than 2.

A significant percentage of Mexico’s smallholders have chosen to work together in democratically run cooperatives that provide members with some of the services and access to resources that other countries’ national institutions often offer. There is also a high percentage of organic-certified farms and cooperatives in the country, despite several years’ struggle with the coffee-leaf-rust epidemic.

Coffee from Mexico is more commonly found in the United States than almost anywhere else in the world, thanks in large part to the very close proximity between the two countries. Primarily, smallholder farmers will harvest, depulp, and ferment their coffee on their own property, bringing it to a mill in order to complete the drying.

NICARAGUA

Capital – Managua

Coffee Port –Corinto

Producers –44,000

National Coffee Authority –Consejo Nacional del Café (CONACAFE)

Approx. Annual Export Volume –1,991,304 bags (137,400 metric tons)

Production –759 kg

Bag Size – 69 kg

La Bodega’s Sourcing Regions

Nueva Segovia

- 1,000–1,600 masl

- 1–14 hectares

- Fruity dark chocolate, mellow to lively citric acidity, toffee

Common Varieties –Bourbon, Catimor, Catuaí, Caturra, Costa Rica 95, Gesha, Maracaturra, Maragogype, Pacamara, Typica

Drying – Patios

Processing Methods

- Washed – Coffee picked, delivered to mill, depulped, fermented (8–12 hours), washed, dried

Harvest Period

- October–March

Arrival Period

- April–July

La Bodega & Nicaragua

The partnerships that La Bodega has been focusing on over the past several years have initiatives in place to improve quality and efficiency for producers in order to mitigate the obstacles in place due to lack of resources or transportation. Currently, La Bodega has two primary relationships in Nicaragua: PRODECOOP, a second-tier cooperative representing 38 smaller growers’ associations across three northwestern departments, and Cafetos de Segovia, a family-run micromill operation that works with a small number of quality-minded friends, family, and specialty-coffee associates in Nueva Segovia.

Coffee Production in Nicaragua